- 9.8.1 MYTH: Extremist candidates will proliferate under a national popular vote.

- 9.8.2 MYTH: Regional candidates will proliferate under a national popular vote.

- 9.8.3 MYTH: It is the genius of the Electoral College that Grover Cleveland did not win in 1888 because the Electoral College works as a check against regionalism.

9.8.1 MYTH: Extremist candidates will proliferate under a national popular vote.

QUICK ANSWER:

- If an Electoral College type of arrangement were essential for avoiding extremist candidates, we would see evidence of extremism in elections (such as gubernatorial elections) that do not employ an Electoral College type of arrangement.

- Actual experience is that extremist candidates are rarely elected in elections in which the winner is the candidate who receives the most votes.

Tara Ross has asserted that if the President were elected by a national popular vote,

“extremist candidates could more easily sway an election.”[250]

Hans von Spakovsky has stated that the National Popular Vote plan:

“could also radicalize American politics.”[251]

History Professor Daniel J. Singal of Hobart and William Smith Colleges warns:

“Tom Golisano’s proposal in his essay ‘Make Every State Matter’ to elect presidents on the basis of the popular vote rather than the Electoral College may sound appealing at first, but would in fact wreak havoc on our national political system in ways that he clearly does not understand.

“Put simply, the Electoral College has turned out to be one of the most brilliant innovations the Founding Fathers devised when writing the Constitution. Its virtue is that it directs our politics to the center of the political spectrum, helping us to avoid the extremism that might otherwise rule the day.

“In states that are up for grabs independent voters in the middle of the political spectrum become crucial. Since those states are usually decided by a few percentage points, the candidates must gear their messages to appeal to those ‘swing voters,’ who by definition are not strong partisans and thus open to either side.”[252] [Emphasis added]

If an Electoral College type of arrangement were essential for avoiding extremist candidates, we would see evidence of Singal’s conjectured “havoc” in elections that do not employ an Electoral College type of arrangement. However, Singal presents no evidence of “havoc” in elections in which the winner is the candidate who receives the most popular votes.

At the time the U.S. Constitution came into effect in 1789, Governors were elected in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut. The idea of popularly electing the Governor was adopted piecemeal, on a state-by-state basis. Today, Governors are elected in 100% of the states.

After over two centuries of actual experience in over 5,000 statewide elections for state chief executive, the lack of moderation in political discourse predicted by Ross, the radicalization of politics predicted by von Spakovsky, and the “havoc” predicted by Singal have yet to materialize. History indicates that extremist candidates are almost never elected in elections in which the winner is the candidate who receives the most popular votes.

U.S. Senators were elected by state legislatures under the original U.S. Constitution. Since ratification of the 17th Amendment in 1913, U.S. Senators have been elected by the people. After nearly 100 years of actual experience under the 17th Amendment, how many U.S. Senators have been extremists?

Given this historical record, there is no reason to expect the emergence of some new and currently unknown political dynamic if the President were elected in the same manner as virtually every other public official in the United States.

Candidates attempting to win any election have a strong incentive to capture “the middle” of their electorate. Counting the votes on a nationwide basis (instead of a statewide basis) would not change this imperative.

Singal provides no explanation as to why “independent voters in the middle of the political spectrum” would not be similarly “crucial” if the President were elected from a nationwide electorate.

Singal also overlooks the fact that there are millions of “swing voters” in the states that get no attention under the current state-by-state winner-take-all system. What is the justification for making “swing voters” in today’s non-battleground states less important than the “swing voters” in battleground states?

Criticism of the National Popular Vote plan on the basis of extremism is yet another example of a criticism that is actually more appropriately applied to the current state-by-state winner-take-all system.

Segregationists such as Strom Thurmond (1948) or George Wallace (1968) won electoral votes in numerous Southern states. Neither Strom Thurmond nor George Wallace had any reasonable expectation of winning the most popular votes nationwide. Under the current state-by-state winner-take-all system, third-party candidates have 51 separate opportunities to find particular states that they might win outright or where they might be able to shift electoral votes from one major party to another.

The current state-by-state winner-take-all system encourages regional third-party candidates such as Strom Thurmond and George Wallace because it offers them the hope of being able to deny a majority of the Electoral College to the major-party candidates, and thereby throw the election of the President to the U.S. House of Representatives or, alternatively, to bargain with the major-party candidates prior to the meeting of the Electoral College.

Footnotes

[250] Written testimony submitted by Tara Ross to the Delaware Senate in June 2010.

[251] Von Spakovsky, Hans. Popular vote scheme. The Foundry. October 18, 2011.

[252] Singal, Daniel J. The genius of the Electoral College. Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. August 23, 2012.

9.8.2 MYTH: Regional candidates will proliferate under a national popular vote.

QUICK ANSWER:

- If an Electoral College type of arrangement were essential for avoiding regional candidates, we should see evidence of regional candidates in elections (such as gubernatorial elections) that do not employ an Electoral College type of arrangement.

- There is no evidence of the emergence of regional candidates or regional parties in statewide elections in which the winner is the candidate who receives the most popular votes.

Tara Ross, an opponent of the National Popular Vote plan, raises the following question:

“What if voters in New York and Massachusetts throw all their weight behind one regional candidate?”[253]

We can easily test Ross’ hypothetical scenario about regional candidates against actual historical experience and facts.

If an Electoral College type of arrangement were essential for avoiding Ross’ conjectured outcome, we would see evidence of regional parties and regional candidates in elections that do not employ an Electoral College.

When Governors are chosen in elections in which the winner is the candidate who receives the most popular votes, we do not see a Philadelphia Party and a Pittsburgh Party competing for the Governor’s office. There is no Eastern Shore Party in Maryland, no Upper Peninsula Party in Michigan, no Northern California Party in California, no Upstate New York Party in New York, and no Panhandle Party in Florida.

Similarly, we do not see regional parties nominating regional candidates to run for the U.S. Senate.

In the real world, ordinary plurality voting discourages the formation of niche parties. Instead, ordinary plurality voting rewards the formation of broad coalitions in which various groups and interests join together in order to win the most votes (and thereby win office).

The reason that ordinary plurality voting has this effect is that a vote cast for a splinter candidate generally produces the politically counter-productive effect of helping the major-party candidate whose views are diametrically opposite to those of the voter.

For example, votes cast for Green Party candidate Ralph Nader enabled Republican George W. Bush to win Florida and New Hampshire in 2000.[254] Votes cast for Libertarian Party candidate Bob Barr enabled Democrat Barack Obama to win North Carolina in 2008.[255]

Based on historical evidence, regional candidates are far more common under the state-by-state winner-take-all system of electing the President than in elections in which the winner is the candidate who receives the most popular votes.

Under the current state-by-state winner-take-all system of electing the President, regional segregationist candidates such as Strom Thurmond (1948) and George Wallace (1968) won electoral votes in various Southern states. None of these third-party candidates had any reasonable expectation of winning a plurality of the popular votes nationwide. The current state-by-state winner-take-all system encourages regional candidacies because such candidates can win certain states outright or can affect the national outcome by shifting electoral votes from one major party to another. The current system gives regional candidates the hope of being able to throw the presidential election into the U.S. House of Representatives or to bargain with the major party candidates before the meeting of the Electoral College in mid-December.

Footnotes

[253] Oral and written testimony presented by Tara Ross at the Nevada Senate Committee on Legislative Operations and Elections on May 7, 2009.

[254] In Florida and New Hampshire in 2000, Ralph Nader received considerably more votes than the margin between George W. Bush (the winner of these two states) and Al Gore (the second-place candidate).

[255] In North Carolina in 2008, Bob Barr (the Libertarian candidate) received considerably more votes than the margin between Barack Obama (the winner of the state) and John McCain (the second-place candidate).

9.8.3 MYTH: It is the genius of the Electoral College that Grover Cleveland did not win in 1888 because the Electoral College works as a check against regionalism.

QUICK ANSWER:

- The state-by-state winner-take-all system does not protect against regionalism.

- In 1888, the state-by-state winner-take-all system gave the White House to a regional candidate who had fewer popular votes nationwide (Harrison) instead of giving it to the regional candidate with more popular votes nationwide (Cleveland).

One of the consequences of the state-by-state winner-take-all rule (i.e., awarding all of a state’s electoral votes to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in each separate state) is that it is possible for a candidate to win the Presidency without winning the most popular votes nationwide.

Of the 57 presidential elections between 1789 and 2012, there have been four elections in which the candidate with the most popular votes nationwide did not win the Presidency (table 1.22).

The election of 1888 between Democrat Grover Cleveland and Republican Benjamin Harrison was one of four such elections.

Trent England (a lobbyist opposing the National Popular Vote compact and Vice-President of the Evergreen Freedom Foundation of Olympia, Washington) has written:

“Because of the Electoral College, Cleveland’s intense regional popularityeven when it gave him a raw total majoritywas not enough to win the presidency.

“Successful presidential campaigns must assemble broad, national coalitions.

“It is the genius of the Electoral College that Grover Cleveland did not win in 1888. The Electoral College works as a check against regionalism and radicalism.

“American politics are more inclusive, moderate, stable, and nationally unified because of the Electoral College.”[256] [Emphasis added]

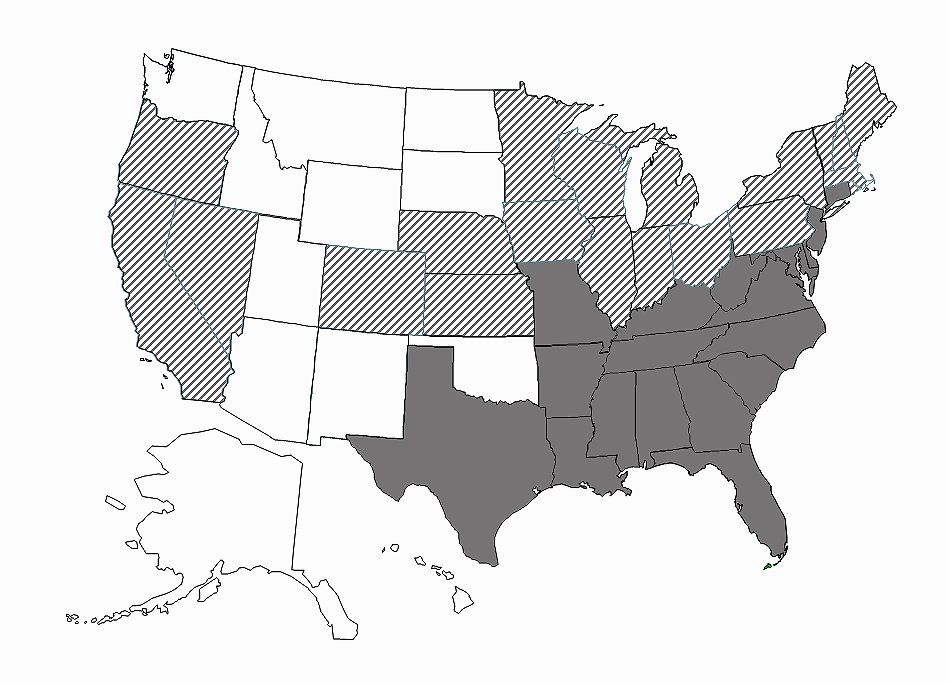

Figure 9.2 shows the distribution of electoral votes in the 1888 presidential election. Democrat Grover Cleveland’s states are shown in black, and Republican Benjamin Harrison’s states are thatched. The white parts of the map represent territories that were not states in 1888.

Figure 9.2 Results of 1888 election

It is certainly true that figure 9.2 shows that the states (in black) carried by the candidate who received the most popular votes nationwide (Grover Cleveland) were concentrated regionally.

However, as the same figure shows, it is equally true that the states (thatched) carried by the second-place candidate (Benjamin Harrison) were regionally concentrated.

How is “the genius of the Electoral College” illustrated by elevating the regional second-place candidate (Benjamin Harrison) to the White House, instead of the regional first-place candidate (Grover Cleveland)?

Moreover, given that Grover Cleveland was a conservative (as evidenced by his record as President starting in 1885 and again in 1893), one wonders how the “wrong winner” outcome of the 1888 election supports Trent England’s claim that “the Electoral College works as a check against radicalism?”

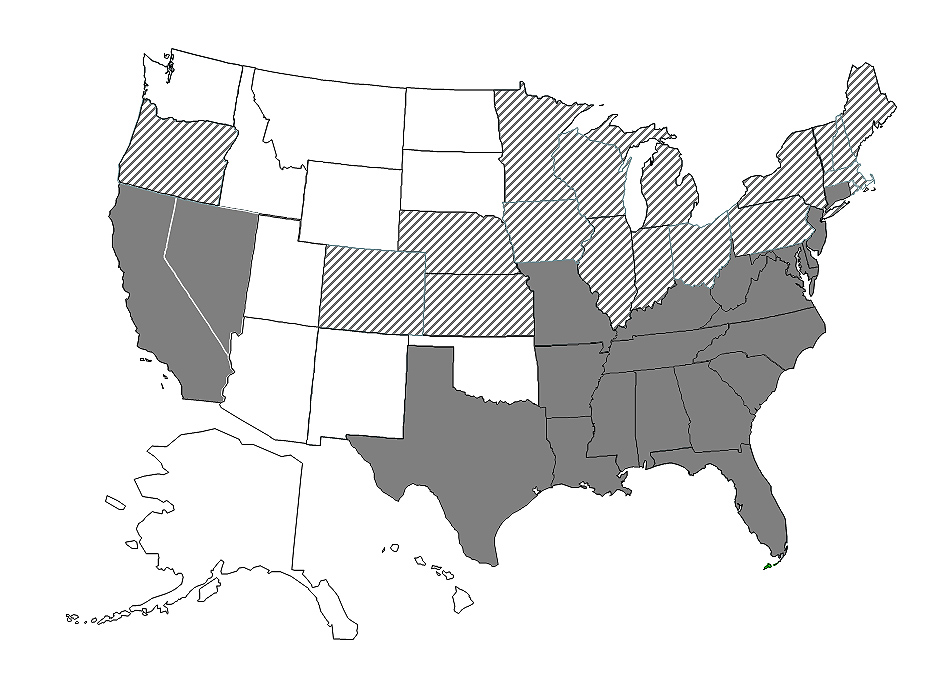

As shown in figure 9.3, the regional pattern of the 1880 election was almost identical to that of the ClevelandHarrison election. In figure 9.3, 1880 Democratic nominee Winfield Hancock’s states are shown in black, and Republican nominee James Garfield’s states are thatched. Indeed, most of the post-Civil-War elections evidenced a regional pattern similar to that of figures 9.2 and 9.3.

Figure 9.3 Results of 1880 election

How is Trent England’s claim that “the Electoral College works as a check against regionalism” illustrated by the election in 1880 of James Garfield, a manifestly regional candidate?

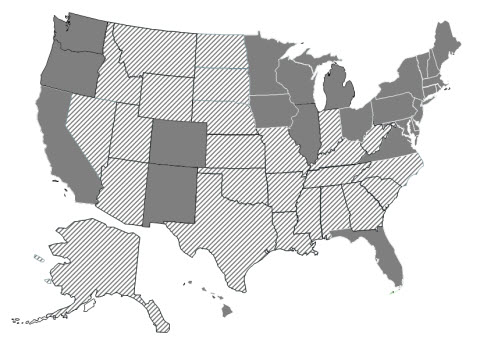

Figure 9.4 shows the results of the 2012 presidential election. Democrat Barack Obama’s states are shown in black, and Republican Mitt Romney’s states are thatched.

Figure 9.4 Results of 2012 election

A comparison of figure 9.4, figure 9.3, and figure 9.2 shows that regionalism was still quite prominent in the nation’s 57th presidential election in 2012just as it was in 1880 and 1888. After 57 presidential elections, when can we expect Trent England’s claim that “the Electoral College works as a check against regionalism” to finally become true?

Footnotes

[256] England, Trent. What Grover learned at (the) Electoral College: American politics are more inclusive, moderate, stable, and nationally unified because of the Electoral College. December 15, 2009. http://www.saveourstates.com/2009/what-grover-learned-at-the-electoral-college/.