Summary

Under the congressional-district method of awarding electoral votes, one electoral vote is awarded to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in each of a state’s congressional districts. The state’s remaining two electoral votes are typically awarded to the statewide winner.

● The congressional-district method could be implemented nationwide by means of a federal constitutional amendment, or individual states can unilaterally implement it (as Maine did in 1969 and as Nebraska did in 1992).

● The congressional-district method would not accurately reflect the nationwide popular vote if used nationwide. In three of the six presidential elections between 2000 and 2020, the winner of the most votes nationwide would not have won the Presidency if the congressional-district method had been applied to election returns.

● The congressional-district method would not make every voter in every state politically relevant. It would worsen the current situation in which three out of four states and most voters in the United States are ignored in the general-election campaign for President. Under the congressional-district method, campaigns would be focused only on the small number of congressional districts that are closely divided in the presidential race. The major-party presidential candidates were within eight percentage points of each other in only 17% of the nation’s congressional districts (72 of 435) in 2020. In contrast, 31% of the U.S. population lived in the dozen closely divided battleground states where the candidates were within eight percentage points of each other in 2020.

● The congressional-district method would not make every vote equal. There are six sources of inequality in the congressional-district method. Each is substantial, and each is considerably larger than the inequalities that the courts have found to be constitutionally tolerable when reviewing the fairness of redistricting.

● 3.81-to-one inequality because of the two senatorial electoral votes that each state receives above and beyond the number warranted by its population,

● 1.72-to-1 inequality because of the roughness of the process of apportioning U.S. House seats among the states,

● 3.76-to-1 inequality because of voter differences in turnout between districts across the country,

● 1.67-to-1 inequality because of voter turnout differences at the state level,

● 1.39-to-1 inequality because of population changes during the decade after each census,

● 7.1-to-1 differences, from district to district, in the number of votes that enable a candidate to win an electoral vote within a state,

● 210-to-1 inequality in the value of a vote based on its ability to decide the national outcome.

● District allocation of electoral votes would magnify the effects of gerrymandering of congressional districts, and increase the incentive to gerrymander.

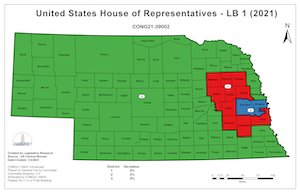

● Presidential campaigns would not be attracted to a state by the congressional-district method, but, instead, only to the relatively few closely divided districts, if any, in a given state. For example, recent presidential campaigns paid attention to Nebraska’s closely divided 2nd congressional district (the Omaha area), while totally ignoring the politically non-competitive rural 1st and 3rd districts. The map below shows Nebraska's three congressional districts. Nebraska's 2nd district is shown in blue.

● The congressional-district method would be difficult to install on a state-by-state basis, because it imposes a substantial first-mover disadvantage on early adopters. A state reduces its own influence if it divides its electoral votes while other states continue to use winner-take-all. Moreover, each additional state that adopts the congressional-district method increases the influence of the remaining “hold-out” winner-take-all states.

● The congressional-district method of awarding electoral votes would make a bad system worse because it would not accurately reflect the nationwide popular vote, would not make every voter in every state politically relevant, and it would not make every vote equal.